男性戀和女性戀

此條目的引用需要清理,使其符合格式。 (2022年6月16日) |

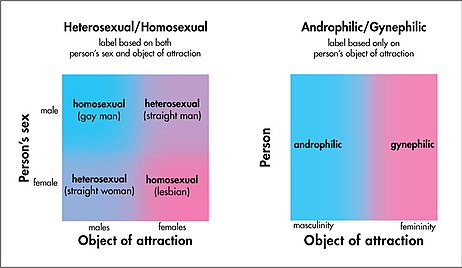

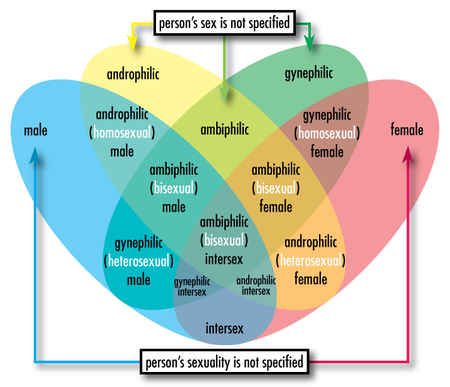

男性戀和女性戀(英語:Androphilia and gynephilia)是性學和行為科學中用來描述性取向的術語,男性戀描述的是對男性和男性氣質產生的喜愛,女性戀則描述了對女性和女性氣質的喜愛。[1][註 1]

這些術語用於識別一個人所產生性衝動的對象,而不將生理性別或性別認同歸因於該人,尤其適合用來描述那些非二元性別人群的性取向,例如雙性人和跨性別者,因為用同性戀和異性戀等術語來描述這些群體的性取向時有可能產生誤導。[3]

早期用法

編輯戀男性

編輯20世紀早期的德國性學家和醫生馬格努斯·赫希菲爾德將男同性戀者分為四類:

根據凱倫·富蘭克林的說法,赫希菲爾德認為戀少年是常見且非病理性的,戀少年和戀成年各占同性戀人口的 45%。[9]男男性行為這個詞偶爾被用作戀男性的同義詞。[10]

戀女性

編輯該術語的詞源最早出現在古希臘語中。在小抒情詩第8篇第60行中,忒奧克里托斯使用了γυναικοφίλιας(gynaikophilias)作為描述宙斯對女性慾望的委婉形容詞。[11][12][13]

西格蒙德·弗洛伊德他對朵拉的案例研究中使用了gynecophilic一詞。[14]他還在跟同行的通信使用過這個詞。[15][16]有時也使用變體拼寫gynophilia。[17]

較為少見的術語gynesexuality也被用作戀女性或女性戀同義詞。[18]

生物學和醫學的替代用途

編輯在生物學中,androphilic有時被用作anthropophilic的同義詞,描述了對人類和非人類動物有雄性宿主偏好的寄生蟲。[19]Androphilic有時也用於描述某些蛋白質和雄激素的受體。[20]

對成年人的性興趣

編輯在赫希菲爾德對男同性戀的四種分類之後,男性戀和女性戀有時會被用於描述根據年齡範圍產生的性衝動,約翰·曼尼稱之為年齡偏好的分類學中。在這樣的分類中,對成年人的產生特別喜好被稱為戀成人癖(adultophilia)[註 2][22]。在這種語境下,androphilia和gynephilia是兩種性別的變體,專門表示「對成年男性的偏好」和「對成年女性的偏好」。[22]丹尼斯·豪伊特指出:

定義主要是一個理論問題,而不僅僅是分類問題,因為分類無論多麼初步,都暗含了一定的理論。弗洛依德等人(1984年)使用拉丁語詞彙按照性別和年齡的維度對性吸引力進行分類:女性戀——對成年生理女性的性興趣;男性戀——對成年生理男性的性興趣。[23]

量表

編輯庫爾特·弗洛因德和貝蒂施泰納於1982年開發了一個關於男性戀-女性戀的量表,其中男性戀有13個指標,女性戀有9個指標。後來雷·布蘭查德於1985年對其進行了修改,稱為改良的男性戀-女性戀指數 (MAGI)。[24]

性別認同和性別表達

編輯馬格努斯·赫希菲爾德最先區分了女性戀、雙性戀、男性戀、無性戀、自戀和自性戀等術語。[25]此後,一些心理學家提出使用跨性別同性戀、異性戀變裝者、非同性戀變性者等詞語。心理生物學家詹姆斯·D·韋因里希描述了這種學術界之間的分裂:

被男性吸引的男跨女變性者(有人稱其為同性戀,而另一些人稱其為男性戀)位於XY表的左下角,以便將他們與右下角是普通的順性別男同性戀區別開。最後是被女性吸引的男跨女變性人(有些人稱之為異性戀,有些人稱之為女性戀或女同性戀)。[26]

老舊術語的批評意見

編輯自20世紀中葉以來,儘管從那時起人們對這些術語表示擔憂,跨性別者使用了同性戀和變性戀相關術語。哈里·本傑明在1966年提到:

....「變性者是同性戀嗎?」如果這個問題如果只能回答「是」和「否」。回答「是」出於考慮生理結構;回答「否」則優先考慮心理性別。 進行了變性手術並且現在的生理結構類似女性,會出現什麼情況?「新女人」還被認為是男同性戀嗎?如果保守謹慎佔據上風,可能回答「是」。如果應用理性和常識,並且將相應的患者視為個體而不是橡皮圖章,則回答「不是」。[27]

許多學術來源,包括類型學一些支持者,批評這種措辭的選擇是令人困惑和有辱人格的。生物學家布魯斯·巴格米爾寫道:「.. 在這個命名法中,「異性戀」或「同性戀」取向的參考點僅僅是個體的遺傳性別。因此,這些標籤忽略了個人對性別認同優先於生理性別的個人感覺。」 巴格米爾繼續對這個術語的方式提出質疑,認為這樣很容易宣傳變性人作為同性戀男性試圖擺脫恥辱。[28]

萊維特和伯傑在1990年表示,「同性戀變性人的標籤對於那些尋求變性的男性來說既令人困惑又充滿爭議。[29][30]批評者認為,「同性戀變性人」一詞是異性戀霸權[31],過時且有侮辱性,因為它按出生時的性別而不是他們後天自認為的性別來給人們貼標籤。本傑明、萊維特和伯傑都在他們自己的論文中使用了這個詞。[32]

性學家約翰·班克羅夫特最近對他使用過這個術語表示反思,因為這在當時用來指代男性變性成的女性是符合標準的術語。他表示現在他會更加注意謹言慎行。[33]性學家查爾斯·艾倫·莫澤同樣對這個術語表達了批評態度。[34]

支持男性戀和女性戀代替同性戀和異性戀術語的意見

編輯心理學家羅納德·朗之萬在1980年代提出要普及男性戀和女性戀的術語使用。[35]康復心理學家斯蒂芬·T·韋格納寫道:「朗之萬就用於表述性非常的術語提出了幾個具體建議。例如,他提出了gynephilic和androphilic的術語來表示無論個人的性別認同或外在着裝如何,都更喜歡的伴侶性別。那些在這方面寫作和研究的人最好採用他這些清晰又簡潔的詞彙。[36]

精神病學家阿尼爾·阿格拉瓦爾解釋了為什麼這些術語在詞彙表中很有用:

男性戀——對成年男性的浪漫取向或性取向。該術語與女性戀一起,需要克服表徵跨性別者性取向的巨大困難。例如,很難確定一個被男性色情吸引的跨性別者是異性戀女性還是同性戀男性;或者被女性吸引的跨性別女人是異性戀男性或女同性戀。任何對它們進行分類的嘗試不僅會引起混亂,而且會在受影響的對象中引起冒犯。在這種情況下,在定義性吸引力時,最好關注他們所喜歡的對象,而不是他們本身的性別。[37]

性學家彌爾頓·戴爾蒙德更喜歡gynecophilia這個詞語[註 3],他寫道:[2]

戴蒙德鼓勵使用男性戀、女性戀和兩性戀描述一個人喜歡的性伴侶。這樣的術語消除了特定影響力的社會群體,而是專注於性行為本身和性喚起的對象。在討論變性人或雙性人的伴侶時,這種用法特別方便。

由於同性戀者、男同性戀者和女同性戀者在許多社會中往往與偏執和排斥有關,因此強調性別的歸屬既恰當又符合社會正義。[38]海倫·博伊德對此表示贊同,他寫道:

非西方文化中的性別

編輯一些研究人員主張使用男性-女性戀術語來避免西方社會性行為概念中固有的偏見。社會學家約翰娜·施密特在描寫薩摩亞文化中的第三性別法阿法芬時指出:[1]

克里斯·波薩、雷·布蘭查德和肯尼斯·扎克(2004)還提出了一個論點,認為法阿法芬可以歸類於「跨性別同性戀」。雖然沒有提供明確的因果關係,但波薩、布蘭查德和扎克使用跨同一詞來指代法阿法芬這種對男性有性衝動的男跨女,這表明性取向和性別認同之間存在明顯的聯繫。提到對於男同也發現了類似的出生次序的影響時,這一事實就加強了這種聯繫。但是沒有考慮從作為女性性別身份中產生(而不是導致)對男性的性取向的可能性。

施密特認為,在承認第三性別的文化中,跨性別同性戀之類的術語與當地的文化標籤不一致。她引用了保羅·瓦西和南希·巴特雷特的論文:「瓦西和巴特雷特揭示了諸如同性戀等概念的文化特殊性,他們繼續使用更科學客觀的術語,男性戀和女性戀,以了解法阿法芬和其他薩摩亞人的性行為。」

研究員薩姆·溫特提出了類似的論點:

諸如同性戀和異性戀(以及「無性戀」和「雙性戀」等)之類的術語是西方的概念。許多歐美以外的地區對這些術語並不熟悉,很難將其翻譯成他們的母語或性世界觀。然而,我藉此機會記錄下,我認為一個男性化的跨性別女人(即一個被男人性吸引的人)仍然是異性戀,因為她被另一個生理性別的成員吸引,而一個女性化的跨性別女人(即一個被女性吸引的人)是同性戀,因為她有同性偏好。我的用法與許多西方文獻(尤其是醫學)相反,後者堅持將女跨男和男跨女都稱為同性戀(實際上分別是跨gay和跨les)。

註釋

編輯參見

編輯參考資料

編輯- ^ 1.0 1.1 Schmidt J (2010). Migrating Genders: Westernisation, Migration, and Samoan Fa'afafine, p. 45 Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 978-1-4094-0273-2

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Diamond M (2010). Sexual orientation and gender identity. In Weiner IB, Craighead EW eds. The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology, Volume 4. p. 1578. John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-17023-6

- ^ Turban, Jack L; de Vries, Annelou LC; Zucker, Kenneth J; Shadianloo, Shervin (2018). "TRANSGENDER AND GENDER NON-CONFORMING YOUTH" (PDF). p. 3. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ Androsexual - What is it? What does it mean? - Taimi wiki. Taimi. [2022-03-22] (英語).

- ^ What Does Androsexual Mean? + Other Androsexual Information To Help You Be A Better Ally!. 2021-11-23 [2022-06-12]. (原始內容存檔於2022-06-19) (英語).

- ^ October 26, Claire Gillespie. 5 Things You Need to Know About Being Androsexual. Health.com. [2022-06-12]. (原始內容存檔於2022-06-20) (英語).

- ^ Wayne R. Dynes, Stephen Donaldson. Encyclopedia of homosexuality, Volume 1. Garland Pub., ISBN 978-0-8240-6544-7

- ^ Sexual anomalies: the origins, nature and treatment of sexual disorders : a summary of the works of Magnus Hirschfeld M. D. Emerson Books, ASIN: B0007ILEF0

- ^ Franklin, K (2010). "Hebephilia: quintessence of diagnostic pretextuality". Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 28 (6): 751–768. doi:10.1002/bsl.934. PMID 21110392.

- ^ Tucker, Naomi (1995). Bisexual politics: theories, queries, and visions. Psychology Press, ISBN 978-1-56024-950-4

- ^ Brown, G. W. (1979). "Depression: A sociologist's view". Trends in Neurosciences, Volume 2, pp. 253–256 doi:10.1016/0166-2236(79)90099-7

- ^ Rummel, Erika (1996). Erasmus on Women, p. 82. University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-7808-7

- ^ Cholmeley RJ (1901). The idylls of Theocritus. G. Bell & Sons, p. 98

- ^ Kahane C (2004). Freud and the passions of the voice. In O'Neill J (2004). Freud and the Passions. Penn State Press, ISBN 978-0-271-02564-3

- ^ Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess, March 23, 1900: "A good-natured and fine person, at a deeper layer gynecophilic, attached to the mother.

- ^ Letter from Sigmund Freud to Sándor Ferenczi, March 25, 1908". Psychoanalytic Electronic Publishing. Retrieved April 13, 2021. I have often seen it so: a woman unsatisfied by a man naturally turns to a woman and tries to invest her long-suppressed gynecophilic component with libido

- ^ Money, John (1986). Venuses Penuses: Sexology, Sexosophy, and Exigency Theory. Prometheus Books, ISBN 978-0-87975-327-6

- ^ Chodorow, Nancy (1999). The Reproduction of Mothering: Psychoanalysis and the Sociology of Gender. University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-22155-0

- ^ Covell G, Russell PF, Hendrik N (1953). Malaria terminology: Report of a drafting committee appointed by the World Health Organization. World Health Organization

- ^ Calandra RS, Podestá EJ, Rivarola MA, Blaquier JA (1974). Tissue androgens and androphilic proteins in rat epididymis during sexual development Steroids, Volume 24, Issue 4, October 1974, Pages 507-518 doi:10.1016/0039-128X(74)90132-9

- ^ Blanchard, R.; Barbaree, H. E.; Bogaert, A. F.; Dickey, R.; Klassen, P.; Kuban, M. E.; Zucker, KJ (2000). "Fraternal birth order and sexual orientation in paedophiles". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 29 (5): 463–478. doi:10.1023/A:1001943719964. PMID 10983250. S2CID 19755751

- ^ 22.0 22.1 Jay R. Feierman: „Reply to Dickemann: The ethology of variant sexology", Human Nature, Springer New York, vol. 3, No 3, September 1992, pp. 279–297

- ^ Howitt D (1995). Introducing the paedophile. In Paedophiles and sexual offences against children. J. Wiley,

- ^ Blanchard, R (1985). "Typology of male-to-female transsexualism". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 14 (3): 247–261. doi:10.1007/bf01542107. PMID 4004548. S2CID 23907992.

- ^ Veale JF, Clarke DE (2008). Sexuality of male-to-female transsexuals. Archives of Sexual Behavior (citing Hirschfeld, 1922, as cited in Freund, 1985)

- ^ Weinrich JD (1987). Sexual landscapes: why we are what we are, why we love whom we love. Scribner's, ISBN 978-0-684-18705-1

- ^ Benjamin H (1966). The Transsexual Phenomenon. The Julian Press ASIN: B0007HXA76 (via Internet Archive)

- ^ Bagemihl B. Surrogate phonology and transsexual faggotry: A linguistic analogy for uncoupling sexual orientation from gender identity. In Queerly Phrased: Language, Gender, and Sexuality. Anna Livia, Kira Hall (eds.) pp. 380 ff. Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-510471-4

- ^ Morgan AJ Jr (1978). Psychotherapy for transsexual candidates screened out of surgery. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 7: 273-282.

- ^ Leavitt F, Berger JC (1990). Clinical patterns among male transsexual candidates with erotic interest in males. Archives of Sexual Behavior, full text Volume 19, Number 5 / October, 1990

- ^ Wahng SJ (2004). Double Cross: Transamasculinity Asian American Gendering in Trappings of Transhood. in Aldama AJ (ed.) Violence and the Body: Race, Gender, and the State. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34171-X

- ^ Leiblum SR, Rosen RC (2000). Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy, Third Edition. ISBN 1-57230-574-6, Guilford Press of New York, c2000.

- ^ Bancroft, John (2008). "Lust or Identity?". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 37 (3): 426–428. doi:10.1007/s10508-008-9317-1. PMID 18431640. S2CID 33178427.

- ^ Moser, Charles (July 2010). "Blanchard's Autogynephilia Theory: A Critique". Journal of Homosexuality (6 ed.). 57 (6): 790–809. doi:10.1080/00918369.2010.486241. PMID 20582803. S2CID 8765340.

- ^ Langevin R (1982). Sexual Strands: Understanding and Treating Sexual Anomalies in Men. Routledge, ISBN 978-0-89859-205-4

- ^ Wegener ST (1984). Male sexual anomalies: the data (review of Sexual Strands) APA Review of Books: Volume 29, Issues 7-12, p. 783. Edwin Garrigues Boring, American Psychological Association

- ^ Aggrawal, Anil (2008). Forensic and medico-legal aspects of sexual crimes and unusual sexual practices. CRC Press, ISBN 978-1-4200-4308-2

- ^ Heath RA (2006). The Praeger handbook of transsexuality: Changing gender to match mindset. Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-275-99176-0

- ^ Boyd H (2007). She's not the man I married: My life with a transgender husband, p. 102. Seal Press, ISBN 978-1-58005-193-4

- ^ Jordan-Young RM (2010). Brain storm: the flaws in the science of sex differences. Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-05730-2

- ^ Winter S (2010). Lost in Transition: Transpeople, Transprejudice and Pathology in Asia. In Chan PCW (ed.) The Protection of Sexual Minorities Since Stonewall: Progress and Stalemate in Developed and Developing Countries. Routledge ISBN 978-0-415-41850-8