针鼹虾属

布氏针鼹虾(学名:Echidnacaris briggsi)为针鼹虾属(学名:Echidnacaris)的唯一一个种,也是模式种。是节肢动物门、恐虾纲、射齿目、筛虾科底下的一个属。[1]原本是位在奇虾属(学名:Anomalocaris )的布氏"奇虾"(学名: "Anomalocaris" briggsi),之后对于针鼹虾的系统发生学证明了针鼹虾并不是奇虾,而是独立一个属。[1]针鼹虾是除了奇虾属的戴氏奇虾(Anomalocaris daleyae)外,唯一一个分布在澳洲的放射齿目动物。[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8]

| 布氏针鼹虾 | |

|---|---|

| |

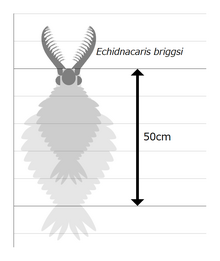

| 针鼹虾的附肢复原图。 | |

| |

| 针鼹虾的全身复原图。 | |

| 科学分类 | |

| 界: | 动物界 Animalia |

| 门: | 节肢动物门 Arthropoda |

| 纲: | †恐虾纲 Dinocaridida |

| 目: | †放射齿目 Radiodonta |

| 科: | †筛虾科 Tamisiocarididae |

| 属: | †针鼹虾属 Echidnacaris Paterson, García-Bellidob & Edgecombe, 2023 |

| 种: | †布氏针鼹虾 E. briggsi

|

| 二名法 | |

| †Echidnacaris briggsi (Nedin, 1995)

| |

发现与命名

编辑针鼹虾的化石是在澳洲南部袋鼠岛的鸸鹋湾页岩被发现的,目前被发现的这些标本被存放在南澳州立博物馆(South Australian Museum)。原本针鼹虾被克里斯多福·内丁(Christopher Nedin)于1995年发表的,当时命名为布氏奇虾( Anomalocaris briggsi)[9],发表十几年后因被怀疑是否为奇虾属,到2023年,针鼹虾才重新归类为新的属。针鼹虾的名字是以生活在澳洲的针鼹俗名-echidna,因为针鼹虾附肢上有许多的小刺;caris是拉丁语的螃蟹,是恐虾纲的常用作学名的字尾。[1]

描述

编辑前附肢

编辑前附肢最长可达到17.5厘米,总共有14节包含连接头部与前附肢的1节柄节和13节螯节。柄节后缘的中间部分具有一个缺口,而在上方和下方分别有比较大和小的圆形突出。每节与每节的中间会有一个非常细的三角形节间膜。第一节往后的节、它的背缘会比腹缘还要长,且愈后会愈短,节的高也是。每一节都有一对从腹侧凸出的内叶,柄节内叶长度占了整个节的高约度95~100%,上面还有更细的辅助刺,往前附肢的外侧边缘有七根小刺,而在内侧仅有一根在刺的最尖端凸出。其它节上的内叶会从直的会稍微弯曲。第一螯节的刺上面的外侧比柄节的还要至少多1根的小刺。第二节到第十节的在外侧的刺增加至13根,而内侧多了六根。[1]

头部骨片

编辑骨片是由两个标本存留下来,且是单独的骨片。头部骨片呈椭圆形,最长可达到85.2毫米,宽则是61.1毫米。[1]

口锥

编辑针鼹虾的口锥外观似圆形,直径7.7厘米。口锥里面的三块大齿板会被不同宽度的八或九块中型齿板隔开,在中央会有小的个开口,有时候发现大齿板会凸进开口。大齿板尺寸接近相等。且在内部的边缘(开口的边缘)有三到四颗齿状突出物,而中型的只有两个。大、中齿板的内半部都许多大小不一的凸出,且凸出物的尖端是指向开口处。[1]

参考资料

编辑- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Paterson, John R.; García-Bellido, Diego C.; Edgecombe, Gregory D. The early Cambrian Emu Bay Shale radiodonts revisited: morphology and systematics. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 2023-01, 21 (1). ISSN 1477-2019. doi:10.1080/14772019.2023.2225066.

- ^ Van Roy, Peter, and Odd Erik Tetlie. "A spinose appendage fragment of a problematic arthropod from the Early Ordovician of Morocco." Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 51.2 (2006): 239-246.

- ^ Vinther, Jakob; Stein, Martin; Longrich, Nicholas R.; Harper, David A. T. A suspension-feeding anomalocarid from the Early Cambrian. Nature. 2014-03, 507 (7493). ISSN 0028-0836. doi:10.1038/nature13010.

- ^ Cong, C; Ma, M; Hou, H; Edgecombe, E; Strausfeld, S. Brain structure resolves the segmental affinity of anomalocaridid appendages. MorphoBank datasets. 2015 [2024-03-14].

- ^ Paterson, John R.; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; García-Bellido, Diego C. Disparate compound eyes of Cambrian radiodonts reveal their developmental growth mode and diverse visual ecology. Science Advances. 2020-12-04, 6 (49). ISSN 2375-2548. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abc6721.

- ^ Nedin, Christopher. Anomalocaris predation on nonmineralized and mineralized trilobites. Geology. 1999, 27 (11). ISSN 0091-7613. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1999)027<0987:aponam>2.3.co;2.

- ^ Lee, Michael S. Y.; Jago, James B.; García-Bellido, Diego C.; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Gehling, James G.; Paterson, John R. Modern optics in exceptionally preserved eyes of Early Cambrian arthropods from Australia. Nature. 2011-06, 474 (7353). ISSN 0028-0836. doi:10.1038/nature10097.

- ^ Daley, Allison C.; Paterson, John R.; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; García‐Bellido, Diego C.; Jago, James B. New anatomical information on Anomalocaris from the Cambrian Emu Bay Shale of South Australia and a reassessment of its inferred predatory habits. Palaeontology. 2013-03-04, 56 (5). ISSN 0031-0239. doi:10.1111/pala.12029.

- ^ Nedin, Christopher. Palaeontology and palaeoecology of the Lower Cambrian Emu Bay Shale Lagerstätten, Kangaroo Island, South Australia (PDF). The Paleontological Society Special Publications. 1992, 6. ISSN 2475-2622. doi:10.1017/s2475262200007814.