維京擴張

此條目可参照英語維基百科相應條目来扩充。 (2021年3月24日) |

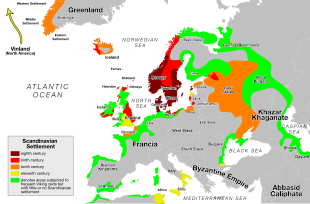

维京人的扩张是指历史上古诺斯人探险家、商人以及勇士在几乎整个北大西洋的航行、探索与殖民。作为强盗,商人和殖民者,他们的足迹南至北非,东至俄罗斯,在地中海远达君士坦丁堡和中东。在西方,红胡子埃里克的后代莱夫·埃里克松带领维京人到达了北美,并在今天的纽芬兰地区的兰塞奥兹牧草地建立了定居点,但未能长期立足。他们也在格陵兰、冰岛、法罗群岛、俄罗斯、不列颠、爱尔兰、诺曼底建立了长期的定居点。

词源

编辑“维京”一词是指所有诺斯殖民者还是仅仅指代其中的强盗是有争议的。

动机

编辑历史学家对维京人扩张的动机有很大争议。

有学者认为维京人最初可能是为了从外部岛屿获得女人而进行航行和劫掠。[1][2][3][4] 11世纪的历史学家Dudo of Saint-Quentin在半幻想著作《诺曼史》第一次提出了这个论述。[5] 有权力且富有的维京男性喜欢拥有多名妻妾,而这种多偶制导致了普通的维京人找不到合适的妻子。他们因此不得不从事危险的活动来得到财富和权力以获取合适的配偶。 [6][7][8] 维京男人经常通过购买或捕捉的方式获取妻子和妾。[9][10] 多偶制增加了雄雄竞争的压力,形成了大量的光棍,他们更愿意冒险以提升地位和获取性资源。 [11][12] 据 Annals of Ulster,821年维京人洗劫了一个爱尔兰村庄并“带走了大量女人作为俘虏”。[13]

另一种理论认为,维京人是为了寻求报复欧洲大陆过去对维京以及维京相关群体的侵略,[14] 尤其是查理大帝的基督教传教运动,其传教方式是杀死所有拒绝受洗的人。[15][16][17][18][19] 支持这个论述的人指出,基督教在斯堪的纳维亚的渗透造成严重的冲突并让挪威陷入长达一个世纪的分裂。[20] 尽管有这个说法,维京人最初的劫掠对象却并非法兰克王国,而是英格兰的修道院。据历史学家 Peter Sawyer, 修道院被抢劫是因为他们是财富聚集地,并且家有余粮,而非任何宗教原因。[21]

还有一种解释是当时维京的人口已经超出土地的农业承载极限。在耕地紧张的挪威西部,这能说的过去,但是斯堪的纳维亚其它地区不太可能会有饥荒。 [22]

有些学者支持另外一种观点,扩张是来自青年膨胀:通常由长子继承所有财富的制度令更小的儿子们不得不通过移民和抢劫来致富。Peter Sawyer指出大部分维京人移民是为了“拥有更多的土地”,而不是因为“没土地没法生存”。[23]

尽管有以上各种理论,这个时期并没有人口膨胀或者农业产出萎缩的确切证据。也不清楚为什么这种扩张是指向海外而不是斯堪的纳维亚半岛广袤的无人森林区,可能是相比清理森林来得到一个农作物生长时间有限的区域,移民或者海上劫掠更加有利可图。

扩张还有可能是因为商路的变更。西欧和欧亚大陆之间的贸易可能在5世纪罗马帝国失去西方省份之后遭到重创,而7世纪伊斯兰的扩张将资源引向了丝绸之路,或许减少了欧洲的贸易机会。[來源請求] 维京扩张开始的时候正是地中海贸易处于最低水平的时期。[來源請求] 扩张在阿拉伯人和法兰克人的土地上开辟了新的商路,并且在法兰克人击溃了弗里西亚舰队后让维京人控制了之前由弗里西亚人控制的市场。[來源請求]

维京人在席卷欧洲扩张中,一个最重要的目的就是获取以及交易白银。[24][25] 时至今日卑尔根和都柏林依然是白银生产的中心。[26][27] 加洛韦宝藏是维京时代用来交易的白银的一个典型。[28]

人口分布

编辑维京人在爱尔兰和不列颠的定居点主要由男性组成,但是也有一些坟墓考古发掘表现出男女数量同等的情况。这可能是因为归类方法的不同。早期的考古学主要靠陪葬品断定性别,而现代考古依赖骨科特征推测性别,并用同位素分析来确定起源(一般情况下无法做DNA取样)。[29][30] 马恩岛这一时期的墓葬显示,男性多数拥有诺斯人名字而女性拥有土著名字。在最初定居冰岛时的古老记载中,提到了爱尔兰和不列颠女人,表明维京探险者有来自不列颠群岛的女性作伴,她们是自愿还是被胁迫不得而知。在西部的岛屿以及斯凯岛的基因学研究也显示维京定居点主要是由维京男性和本地女性组成的。[來源請求]

但也并非所有的维京定居点都是由男性建立。在设得兰群岛的基因学研究发现,到达这个区域的移民家庭单位,一般同时有维京男人和女人。[31]

可能的原因是,设得兰群岛这样靠近斯堪的纳维亚的区域,适合家庭移民。而更北部和更西部的边疆定居点更适合未婚男性殖民者。[32]

参考资料

编辑- ^ Hrala, Josh. Vikings Might Have Started Raiding Because There Was a Shortage of Single Women. ScienceAlert. [2019-07-19]. (原始内容存档于30 May 2019) (英国英语).

- ^ Choi, Charles Q.; November 8, Live Science Contributor |; ET, 2016 09:07am. The Real Reason for Viking Raids: Shortage of Eligible Women?. Live Science. [2019-07-21]. (原始内容存档于29 July 2019).

- ^ Sex Slaves – The Dirty Secret Behind The Founding Of Iceland. All That's Interesting. 2018-01-16 [2019-07-22]. (原始内容存档于22 July 2019) (美国英语).

- ^ Kinder, Gentler Vikings? Not According to Their Slaves. National Geographic News. 2015-12-28 [2019-08-02]. (原始内容存档于2 August 2019).

- ^ David R. Wyatt. Slaves and Warriors in Medieval Britain and Ireland: 800–1200. Brill. 2009: 124 [2022-02-17]. ISBN 978-90-04-17533-4. (原始内容存档于2022-04-06).

- ^ Viegas, Jennifer. Viking Age triggered by shortage of wives?. msnbc.com. 2008-09-17 [2019-07-21]. (原始内容存档于23 July 2019) (英语).

- ^ Knapton, Sarah. Viking raiders were only trying to win their future wives' hearts. The Telegraph. 2016-11-05 [2019-08-01]. ISSN 0307-1235. (原始内容存档于1 August 2019) (英国英语).

- ^ New Viking Study Points to "Love and Marriage" as the Main Reason for their Raids. The Vintage News. 2018-10-22 [2019-08-02]. (原始内容存档于2 August 2019) (英语).

- ^ Karras, Ruth Mazo. Concubinage and Slavery in the Viking Age. Scandinavian Studies. 1990, 62 (2): 141–162. ISSN 0036-5637. JSTOR 40919117.

- ^ Poser, Charles M. The dissemination of multiple sclerosis: A Viking saga? A historical essay. Annals of Neurology. 1994, 36 (S2): S231–S243. ISSN 1531-8249. PMID 7998792. S2CID 36410898. doi:10.1002/ana.410360810 (英语).

- ^ Raffield, Ben; Price, Neil; Collard, Mark. Male-biased operational sex ratios and the Viking phenomenon: an evolutionary anthropological perspective on Late Iron Age Scandinavian raiding. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2017-05-01, 38 (3): 315–24. ISSN 1090-5138. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.10.013 .

- ^ Vikings may have first taken to seas to find women, slaves. Science | AAAS. 2016-04-13 [2019-07-19]. (原始内容存档于27 July 2019) (英语).

- ^ Andrea Dolfini; Rachel J. Crellin; Christian Horn; Marion Uckelmann. Prehistoric Warfare and Violence: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. Springer. 2018: 349 [2022-02-17]. ISBN 978-3-319-78828-9. (原始内容存档于2022-04-24).

- ^ Einhards Jahrbücher, Anno 808, p. 115.

- ^ Bruno Dumézil, master of Conference at Paris X-Nanterre, Normalien, aggregated history, author of Conversion and freedom in the barbarian kingdoms, 5th – 8th centuries (Fayard, 2005)

- ^ "Franques Royal Annals" cited in Peter Sawyer, The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings, 2001, p. 20.

- ^ Dictionnaire d'histoire de France – Perrin – Alain Decaux and André Castelot. 1981. pp. 184–85 ISBN 2-7242-3080-9.

- ^ Les vikings : Histoire, mythes, dictionnaire R. Boyer, Robert Laffont, 2008, p. 96 ISBN 978-2-221-10631-0

- ^ François-Xavier Dillmann, Viking civilisation and culture. A bibliography of French-language, Caen, Centre for research on the countries of the North and Northwest, University of Caen, 1975, p. 19, and Les Vikings – the Scandinavian and European 800–1200, 22nd exhibition of art from the Council of Europe, 1992, p. 26.

- ^ History of the Kings of Norway by Snorri Sturlusson translated by Professor of History François-Xavier Dillmann, Gallimard ISBN 2-07-073211-8 pp. 15–16, 18, 24, 33, 34, 38.

- ^ Sawyer, Peter. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. Oxford: OUP. 2001: 96. ISBN 978-0-19-285434-6.

- ^ Sawyer, Peter. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. Oxford: OUP. 2001: 3. ISBN 978-0-19-285434-6.

- ^ Sawyer, Peter. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. Oxford. 1997: 3.

- ^ Datahub of ERC funded projects. erc.easme-web.eu. [2021-10-19]. (原始内容存档于2022-02-17).

- ^ Silver and the Origins of the Viking Age: An ERC project. sites.google.com. [2021-10-19]. (原始内容存档于2022-02-18) (美国英语).

- ^ Viking Ireland | Archaeology. National Museum of Ireland. [2021-10-19]. (原始内容存档于2022-06-10) (英语).

- ^ ..The Silver Treasure | KODE.... kodebergen.no. [2021-10-19]. (原始内容存档于2021-10-27).

- ^ History, Scottish; read, Archaeology 15 min. The Galloway Hoard in the context of the Viking-age. National Museums Scotland. [2021-10-19]. (原始内容存档于2022-03-19) (英语).

- ^ Shane McLeod. "Warriors and women: the sex ratio of Norse migrants to eastern England up to 900 AD (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)" 18 Jul 2011. Early Medieval Europe, Volume 19, Issue 3, pp. 332–53, August 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0254.2011.00323.x Web PDF (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) Quote:"These results, six female Norse migrants and seven male, should caution against assuming that the great majority of Norse migrants were male, despite the other forms of evidence suggesting the contrary."

- ^ G. Halsall, "The Viking presence in England? The burial evidence reconsidered" in D. M. Hadley and J. Richards, eds, Cultures in Contact: Scandinavian Settlement in England in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries (Brepols: Turnhout, 2000), pp. 259–76. ISBN 2-503-50978-9.

- ^ Roger Highfield, "Vikings who chose a home in Shetland before a life of pillage", Telegraph, 7 Apr 2005, accessed 12 Dec 2012 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Heredity – Human migration: Reappraising the Viking Image. [Jun 7, 2020]. (原始内容存档于2017-01-25).