昆迪博亚卡高原

昆迪博亚卡高原(西班牙語:Altiplano Cundiboyacense)是哥伦比亚东部山区的一处高原,为昆迪纳马卡省和博亚卡省的一部分,平均海拔2,600米,最高海拔可达到4,000米。昆迪博亚卡高原分为三大亚区:波哥大的热带草地、乌瓦特和奇金基拉的谷地,以及杜伊塔马和索加莫索的谷地。

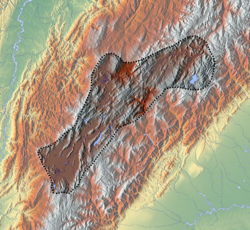

| 昆迪博亚卡高原 Altiplano Cundiboyacense | |

|---|---|

| |

地形图 | |

| 坐标:5°25′08″N 73°25′17″W / 5.41889°N 73.42139°W | |

| 位置 | |

| 山脉 | 安地斯山脈 |

| 属于 | 哥倫比亞東部山脈 |

| 年代 | 中新世至近世 |

| 造山运动 | 安第斯 |

| 面积 | |

| • 总计 | 25,000 km2(9,700 sq mi) |

| 海拔 | 2,600 公尺(8,500 英尺) |

| 最高海拔 | 4,000米(13,000英尺) |

| 火山场 | 派帕-伊萨火山群 |

| 最近喷发 | 皮亚琴期 |

该高原之名称“昆迪博亚卡”是昆迪纳马卡省和博亚卡省两个省区名的组合词。

气候

编辑昆迪博亚卡高原的平均气温为14 °C(57 °F),最低气温0 °C(32 °F),最高气温达到24 °C(75 °F)。十二月到次年三月为干季,四月、五月、九月、十月和十一月多雨;六月至八月常有强风。冰雹天气较常见[1]。

昆迪博亚卡高原有着独特的帕拉莫生态系统,是哥伦比亚主要的帕拉莫生态系统分布区之一,“帕拉莫”(páramo)意为荒地[2]。博亚卡省的帕拉莫荒地面积占全国面积的18.3%[3]。昆迪博亚卡高原南邻世界最大的帕拉莫荒地——苏马帕斯荒地[4]。

主要城市

编辑昆迪博亚卡高原最重要的城市即哥伦比亚首都波哥大。除波哥大外的其他城市如下(从东北至西南排序):

参见

编辑参考文献

编辑- ^ Climates of various cities of Colombia. [2020-04-04]. (原始内容存档于2019-03-29).

- ^ Five unmissable Colombian páramos begging to be explored. [2020-04-04]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-29).

- ^ Nieto Escalante et al., 2010, p.75

- ^ Wills et al., 2001, p.117

书目

编辑- Botiva Contreras, Álvaro; Ana María Groot de Mahecha; Eleonor Herrera, and Santiago Mora. 1989. Colombia Prehispánica – La Altiplanicie Cundiboyacense – Prehispanic Colombia – the Altiplano Cundiboyacense. Biblioteca Luís Ángel Arango. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Barney Duran, Victoria Eugenia. 2011. Biodiversidad y ecogeografía del género Lupinus (Leguminosae) en Colombia (MSc.), 1–81. Universidad Nacional. Accessed 2016-11-17.

- Calvachi Zambrano, Byron. 2012. Los ecosistemas semisecos del altiplano cundiboyacense, bioma azonal singular de Colombia, en gran riesgo de desaparición – The semi-arid ecosystems of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, bioma of Colombia, at great risk of disappearance. Mutis 2. 26–59

- Hoorn, Carina; Javier Guerrero; Gustavo A. Sarmiento, and Maria A. Lorente. 1995. Andean tectonics as a cause for changing drainage patterns in Miocene northern South America. Geology 23. 237–240

- Hoyos, Natalia; O. Monsalve; G.W. Berger; J.L. Antinao; H. Giraldo; C. Silva; G. Ojeda; G. Bayona, and J. Escobar and C. Montes. 2015. A climatic trigger for catastrophic Pleistocene–Holocene debris flows in the Eastern Andean Cordillera of Colombia. Journal of Quaternary Science 30. 258–270

- Monsalve, Maria Luisa; Nadia R. Rojas; Francisco A. Velandia P.; Iraida Pintor, and Lina Fernanda Martínez. 2011. Caracterización geológica del cuerpo volcánico de Iza, Boyacá – Colombia. Boletín de Geología _. 117–130

- Montoya Arenas, Diana María, and Germán Alfonso Reyes Torres. 2005. Geología de la Sabana de Bogotá, 1–104. INGEOMINAS.

- Nieto Escalante, Juan Antonio; Claudia Inés Sepulveda Fajardo; Luis Fernando Sandoval Sáenz; Ricardo Fabian Siachoque Bernal; Jair Olando Fajardo Fajardo; William Alberto Martínez Díaz; Orlando Bustamante Méndez, and Diana Rocio Oviedo Calderón. 2010. Geografía de Colombia – Geography of Colombia, 1–367. Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi.

- Sarmiento Rojas, L.F.; J.D. Van Wees, and S. Cloetingh. 2006. [ Mesozoic transtensional basin history of the Eastern Cordillera, Colombian Andes: Inferences from tectonic models]. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 21. 383–411. Accessed 2020-04-04.

- Cardale de Schrimpff, Marianne. 1985. Ocupaciones humanas en el Altiplano Cundiboyacense – Human occupations on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense. Biblioteca Luís Ángel Arango. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Correal Urrego, Gonzalo. 1990. Aguazuque: Evidence of hunter-gatherers and growers on the high plains of the Eastern Ranges, 1–316. Banco de la República: Fundación de Investigaciones Arqueológicas Nacionales. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Groot de Mahecha, Ana María. 1992. Checua: Una secuencia cultural entre 8500 y 3000 años antes del presente – Checua: a cultural sequence between 8500 and 3000 years before present, 1–95. Banco de la República. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Silva Celis, Eliécer. 1962. Pinturas rupestres precolombinas de Sáchica, Valle de Leiva – Pre-Columbian rock art of Sáchica, Leyva Valley. Revista Colombiana de Antropología X. 9–36. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Villarroel, Carlos; Ana Elena Concha, and Carlos Macía. 2001. El Lago Pleistoceno de Soatá (Boyacá, Colombia): Consideraciones estratigráficas, paleontológicas y paleoecológicas. Geología Colombiana 26. 79–93

- Paepe, Paul de, and Marianne Cardale de Schrimpff. 1990. Resultados de un estodio petrológico de cerámicas del Periodo Herrera provenientes de la Sabana de Bogotá y sus implicaciones arqueológicas – Results of a petrological study of ceramics form the Herrera Period coming from the Bogotá savanna and its archaeological implications. Boletín Museo del Oro _. 99–119. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Argüello García, Pedro María. 2015. Subsistence economy and chiefdom emergence in the Muisca area. A study of the Valle de Tena (PhD), 1–193. University of Pittsburgh. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Boada Rivas, Ana María. 2006. Patrones de asentamiento regional y sistemas de agricultura intensiva en Cota y Suba, Sabana de Bogotá (Colombia) – Regional settlement patterns and intensive agricultural systems in Cota and Suba, Bogotá savanna (Colombia), 1–181. Banco de la República. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Broadbent, Sylvia M.. 1968. A prehistoric field system in Chibcha territory, Colombia. Ñawpa Pacha: Journal of Andean Archaeology 6. 135–147

- Daza, Blanca Ysabel. 2013. Historia del proceso de mestizaje alimentario entre Colombia y España - History of the integration process of foods between Colombia and Spain (PhD), 1–494. Universitat de Barcelona.

- Francis, John Michael. 1993. "Muchas hipas, no minas" The Muiscas, a merchant society: Spanish misconceptions and demographic change (M.A.), 1–118. University of Alberta.

- García, Jorge Luis. 2012. The Foods and crops of the Muisca: a dietary reconstruction of the intermediate chiefdoms of Bogotá (Bacatá) and Tunja (Hunza), Colombia (M.A.), 1–201. University of Central Florida. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Groot de Mahecha, Ana María. 2008. Sal y poder en el altiplano de Bogotá, 1537–1640, 1–174. Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

- Kruschek, Michael H. The evolution of the Bogotá chiefdom: A household view (PhD) (PDF) (PhD). University of Pittsburgh: 1–271. 2003 [2016-07-08]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2016-08-15).

- Langebaek Rueda, Carl Henrik. 1985. Cuando los muiscas diversificaron la agricultura y crearon el intercambio – When the Muisca diversified the agriculture and created the exchange. Boletín Cultural y Bibliográfico 22. 1–8. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Ocampo López, Javier. 2007. Grandes culturas indígenas de América – Great indigenous cultures of the Americas, 1–238. Plaza & Janes Editores Colombia S.A..

- Francis, John Michael. 2002. Población, enfermedad y cambio demográfico, 1537-1636. Demografía histórica de Tunja: Una mirada crítica. Fronteras de la Historia 7. 13–76

- Langebaek Rueda, Carl Henrik. 1995c. De cómo convertir a los indios y de porqué no lo han sido. Juan de Varcarcel y la idolatría en el altiplano cundiboyacense a finales del siglo XVII – How to convert the indians and why they didn't. Juan de Varcarcel and the idolatry on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense at the end of the 17th century. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología 11. 187–234

- Martínez Martín, A. F., and E. J. Manrique Corredor. 2014. Alimentación prehispánica y transformaciones tras la conquista europea del altiplano cundiboyacense, Colombia. Revista Virtual Universidad Católica del Norte 41. 96–111. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Hurtado Caro, José Próspero. 2012. Monguí – Boyacá – Colombia.

- Wills, Fernando. 2001. Nuestro patrimonio – 100 tesoros de Colombia – Our heritage – 100 treasures of Colombia, 1–311. El Tiempo.